The Lauren Rogers Museum of Art opened in 1923 to commemorate Lauren Eastman Rogers, son and grandson to prominent founding fathers of Laurel, MS. Following Lauren Roger’s untimely death in… Continue reading Lauren Rogers Museum of Art

Historic Location Option: Maverick State

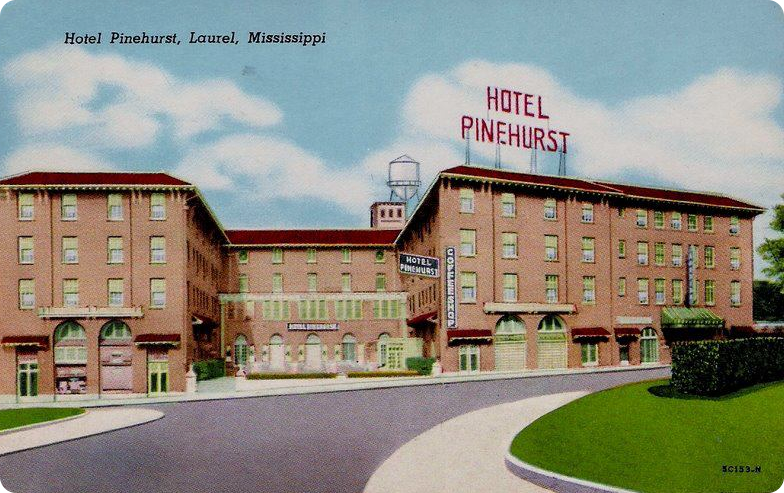

Hotel Pinehurst

Constructed in 1914, the Hotel Pinehurst was owned and operated by T.B. Horton until 1939. The hotel included over 100 rooms, a grand lobby and entranceway, and a number of… Continue reading Hotel Pinehurst

Laurel Machine and Foundry

Today, Laurel Machine & Foundry Co. operates as a general contract shop, offering a full range of services including: Company History 1904 – Laurel Machine and Foundry Co. established as a… Continue reading Laurel Machine and Foundry

Leontyne Price

Mary Violet Leontyne Price was born on February 10, 1927, in Laurel, Mississippi, to James Anthony Price, a carpenter, and Kate Baker Price, a midwife with a beautiful singing voice.… Continue reading Leontyne Price

Lindsey Eight Wheel Log Wagon Company

After John Lindsey patented the Lindsey Eight Wheel Log Wagon in 1899, he and his brother, S.W. Lindsey, moved to Laurel, Mississippi where they organized the Lindsey Wagon Company. While… Continue reading Lindsey Eight Wheel Log Wagon Company

Oak Park School

The lumber barons of Laurel differed from other mill owners in the region in another quite important manner. Whereas many of the other mill owners were content to rely on… Continue reading Oak Park School

Masonite International Corporation

Masonite International Corporation is a leading manufacturer of doors and door components, based in Mississauga, Canada. Approximately two-thirds of sales come from interior doors. All told, the company each day… Continue reading Masonite International Corporation

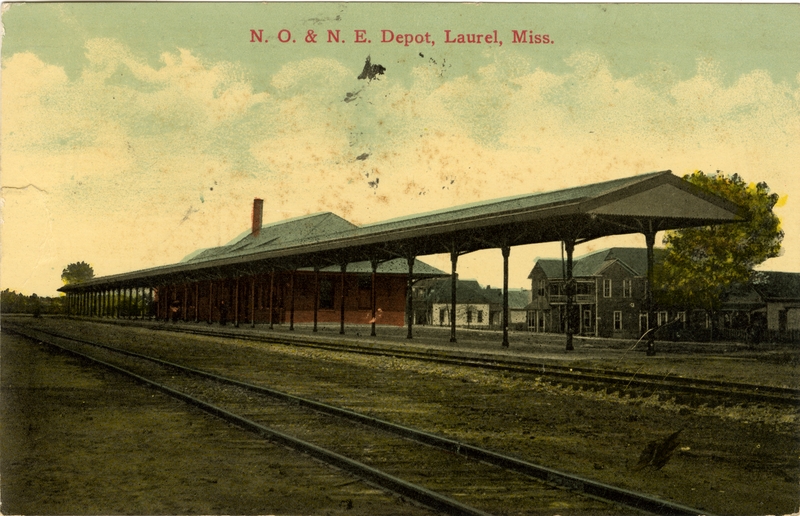

New Orleans & Northeastern Rail Road

The idea of a railroad running the 196 miles between Meridian and New Orleans was conceived by William H. Hardy. In his autobiography, Hardy explains his dream: “In 1868, while… Continue reading New Orleans & Northeastern Rail Road

Eastman, Gardiner & Co. Building

Eastman, Gardiner & Company sawmill plant occupied 26,000 acres of timberland on the south side of downtown Laurel, Mississippi from 1891 until 1937. The Eastman, Gardiner & Company plant contained… Continue reading Eastman, Gardiner & Co. Building